Ahmad Ghossein

Serotonin, Benzine and a Renegade Body

27 September 2023 - 7 December 2023

When a wave overwhelms you, you forget your voice and surrender to the void.

The tempestuous events have penetrated my being, reaching deepest within; hitting that infinitesimal point in the relentlessly throbbing nerve; whose beats never cease to haunt me; even when I shut my eyes.

I have been thrashed by momentous waves since 2019; my body pulled and tossed by the events in Beirut; my legs carried me to the Corniche; my hands alternated between flipping the circuit breaker and carrying gallons of gasoline; my breathing is busy drawing in rancid air in my two panicked lungs; now we have all become hunchbacks; my eyes greeted the owner of the neighborhood’s supplier of power with contrived gratitude. How can I not be grateful when he, alone, holds the keys to the propellor for my every day.

I am estranged from whom I have been prior to this time.

And because the body is treacherous, it compels me into its favorite somatic game. It reminds me of my limits; my physical, mechanical limits. It warns me:

I am your limits.

Do not listen to your mind because I will defeat it, just as I have defeated before those you loved. Your mind is incapable of comprehending what you are going through.

I am the body; I am your supreme god.

I am the transient force capable of eliminating you in the blink of an eye. Do not listen to your mind, which tempts you into thinking reality is worse than it actually is. It is only trying to rob you and me of our pleasure hormones.I am here, and here I shall remain. And whenever you get carried too deep in a depressive cycle, I will prompt the heart to beat faster, so fast, that you will end up at the door of the hospital’s ER. We, as members of the body committee, will order your inhalations and exhalations to halt until you are forced to run every morning to regain your strength.As soon as the brain attempts to attune the flow of happiness hormones to the rhythm of this collapsing reality, we will rise as one to thwart its efforts. We will mute the voice speaking words, heavy with grief, so that you do not choke on your grief-laden words. We know this wicked organ called the brain is most active at night. This traitor abducts the body’s need for respite by playing tricks on you, robbing us all of our rightful neurotransmitters: of joy, of rest, of sleep.

As the collapse worsens, so does my impotence. I can no longer bear all that we have endured, and I am taken by my inner self. Or to be more precise, I have become attuned to the rhythm of the city. Brow-beaten and resigned, I walk around the streets. Whenever the panic in the city intensified, whether over the fuel crisis or the dwindling dollar, so did my panic. Breathing became harder, and my body and brain cells warred on ceaselessly. And when the situation briefly stabilized or we adjusted to it, my rhythm would calm down and so did my heartbeats. Every act is a solitary act, like everyone else around me, I am busy trying to preserve the limited reservoir of my happiness hormones still left in me, trying my best to control my breathing.

The financial collapse was only the beginning of a series of shocks. I spent hours thoroughly reviewing my bank account. I recall a friend, who repeatedly advised me to set up a saving account for my retirement. He was obsessed and terrified from the idea that we, the self-employed, have no social security or protection for our old days. He would put away a monthly sum and deposit it at a bank that convinced him into thinking his retirement was safe with them. He lost all his money, cheated by the perfidious bank. In one year, he seems to have aged by twenty. He reached his retirement age much faster than expected.

I spent hours examining my bank account in Lebanese Pounds, calculating its dwindling value day by day. I decided to turn my money into an artwork titled “How to Make your Money Sell” which uses sliced bills of 1,000, 5,000, 10,000 and 20,000 Lebanese Pounds, bills which have now become useless. The sum of these worthless bills would amount to the money the bank has stolen from me. This artwork is dedicated to my friend whose lifespan was practically halved by his banker.

Running in circles, until we got bored of ourselves, our faces, our own grief. I felt I was thinking from my voice, perhaps it would end this warfare called anxiety, or despair, or fear, or panic. In response, in an attempt to survive or end the conflict between the warring members of the body committee and the sum of my nerve cells, I shifted my focus elsewhere to distract myself.

This is how I got attached to specific events or pieces of news, making them the center of my attention. I collected the most sordid, strange, incomprehensible news items. A journalist who claims to smell the natural gas stored hundreds of kilometers below the sea’s bedrock; the arrival of a new self-proclaimed prophet; a generator owner cuts off the power supply to a police station because bills have not been paid; the US embassy recalls sixteen police dogs it had donated to our national police, because they became under-nourished.

I collected all of these news, real stories, stories that are not imagined or invented. One morning, I woke up to news that the Minister of Education is suggesting hauling speakers on roaming cars around the city to deliver classes for kids locked in their homes during the quarantine. Real stories that intensified my urge to take another tab of Xanax.

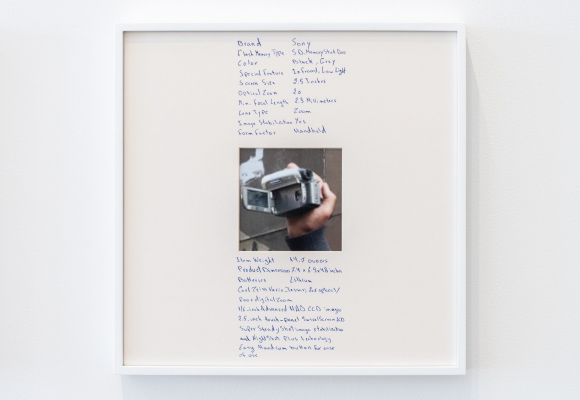

The video work titled “So your heart aches, huh?” or “The Pit” is centered around a personal text that narrates the various manners I tried to keep myself together through the collapse, mostly through my obsession with the work of hormones, especially hormones that arouse feelings of joy, contentment, and satisfaction, like dopamine and oxytocin. I was obsessed with learning how to raise their levels in my body while witnessing the chaos and madness of the country and the frenzied audacity of the media and its “news”.

I got used to anticipating the absurd events that would happen to me on a daily basis, like my desperate attempt to find gasoline for my car during the fuel crisis. I went to the ‘underground’ black market in Dahyeh, Beirut’s southern suburbs. I bought a gallon of gasoline, “sealed” as the young seller told me. It’s an “original” apparently. How strange is this word in this context? I went with him to see how he seals gallons, fills them up and brings them to his clients—fresh out of the black market. A sealed water gallon filled with gasoline in a country where no water reaches the houses, and no gasoline reaches the people. I ruminate over the different shapes and sizes of the plastic bottle cut in half and the short tube tied to it. It has become a tool to drip the gasoline into the fuel inlet. Almost no car today is without this handy tool.

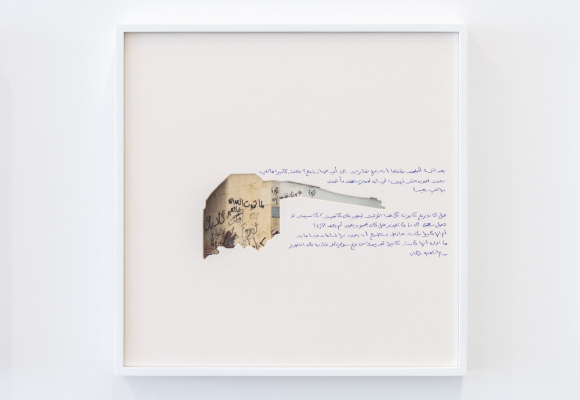

After setting up the works of this exhibition, I noticed that its timeline oscillates between the beginning of the uprising, the ongoing collapse, and a work that attempts to engage with a previous artwork by the artist Marwan Richmaoui. Is “Fragments from Beirut 2019…” emerging from Beirut Caoutchouc, a conversation with it, or a rupture from it? In this new version, the building blocks and neighborhoods are not quite discernable, they are fragmented and disintegrating, as I see Beirut now.

I ran into Mounir Sabra on my way out of a yoga class right after the Beirut port explosion. The country endured yet another collective trauma after this catastrophe. No two people would meet without relaying the events of that hour: their exact location when half the city blew up.

We exchanged words briefly, then he immediately shifted to talking about his experience of that moment, and expressing relief that I was safe (alive). When he finished recounting the events, he pulled up photos from his phone of his destroyed home and the buildings surrounding it. He explained how he escaped and the horrors he witnessed.

One particular photo caught my attention. It was a picture of a piece of rubber with a map of Nejmeh Square and the Serail in downtown Beirut, a picture from a work I knew well. Mounir said this piece was still in his house. He didn’t know how it got there—it was probably blown away with the shards of wood and glass that ended up in the wreckage of his house. When I told him this was a piece from an artwork, Mounir remembered that in the giant building near his house lived a well-known collector called Henry Salloum. This likely belonged to some work in his collection. Mounir and I went to visit Mr. Salloum carrying the broken piece. He had bought the artwork titled Beirut Caoutchouc and dedicated an entire room for its display. Beirut Caoutchouc was also blown to pieces from the blast. Only a few of its parts remain, scattered here and there. The largest piece had landed in Mounir’s house. Henry refused to take it back. He said he was leaving Lebanon for good, taking with him only a few artworks that had survived unscathed. This story is fiction. Reality is, however, stranger than fiction. The only true fact in this story is that the blast happened.

This exhibition includes works that reflect the current circumstances in all their frenzy and lethal chaos.

Translation and copy editing:

Hussein Nassereddine

Nourhane Kazak