Lamia Joreige

Under-Writing Beirut

10 October 2017 - 29 December 2017

In her multi-chaptered project Under-Writing—Beirut, Lamia Joreige investigates historically and personally significant locations within Beirut’s present. Like a palimpsest, the project incorporates various layers of time and existence, creating links between the traces that record such places’ previous realities and the fictions that reinvent them. Mathaf (2013) was the first chapter. Nahr, the second chapter (2013-2016), and Ouzai, the third chapter (2017-ongoing), are both presented for the first time in Lebanon in the artist’s solo exhibition at Marfa’.

How has political decision-making or lack thereof transformed these areas and the communities that inhabit them? How does this translate into everyday life, making these areas spaces where Lebanon’s most crucial problems converge? What kind of narratives can emerge from and be triggered by such places, rather than represent them?

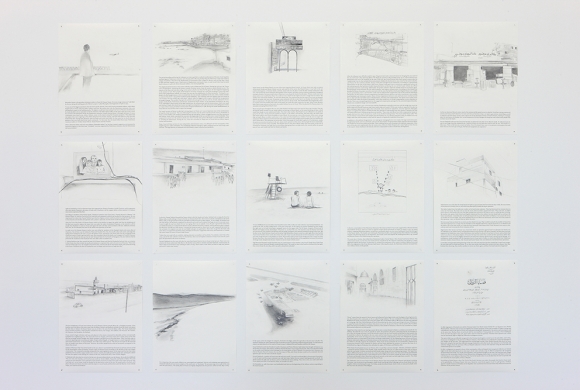

In Under-Writing Beirut—Nahr (The River), Lamia Joreige uncovers the different facets of Beirut’s River with its recent and rapid transformations, from dumping ground to a place scheduled for ambitious development. While defining the eastern edge of the city, the river now flowing weakly both connects and separates Beirut and its suburbs. The work invites reflection on the interwoven narratives of the river, its surroundings and the people who live and work around it, particularly the urban area named Jisr el Wati.

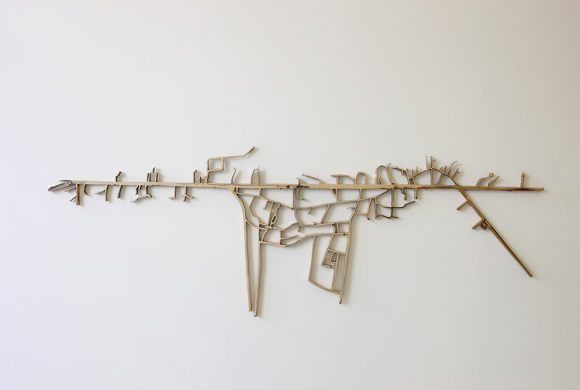

Joreige’s series of drawings The River (2015-2017) are inspired from various maps of the river. In her three-channel video installation After the River (2016), she explores notions of borders and landscape and reflects on the diverse migrant population that has historically settled along the river’s banks. She studies the potential for gentrification of this area, one of the few remaining unexploited spaces in the capital. The area saw the rapid development of what has long been a derelict piece of land into a place of interest for art practitioners and recently, the site of high-rise residential constructions. The various plans to rehabilitate the river and the influx of refugees and migrants to the ever–expanding city make the future of the river and the fate of all the communities living in the area unknown.

It is in a similar spirit that the project Under-Writing Beirut takes up the histories and dynamics of Ouzai. For a long time, this area south of Beirut known as Roumoul (the dunes) was unoccupied and undefined. In the 1950s, as the city outgrew its ramparts, the land on its edges, useless for agriculture, became more valuable. The southern suburbs saw some substantial state investment as part of a growing, modernizing metropolis.

The first inhabitants of Ouzai were almost all rural Lebanese driven towards Beirut by a changing economy. From the nineteenth century onward, the continual lack of legal clarity over the ownership of land in Ouzai allowed the tension to fester in the 50’s, culminating in a trial, where it was finally decided that the land was private and not owned by the municipality of Bourj al Brajneh. This caused a spurt of informal (and, according to the decision of the trial, illegal) construction. The contested ownership, along with the weak regulatory power of the state and the fact that many properties were owned by a large number of co-owners, created a favorable ground for people who, looking for a better life near the capital or later fleeing the violence of the war, would settle there, most of them illegally.

The period preceding and during the Lebanese war saw a radical transformation of the area. The regular bombarding and then invasion

of the southern villages of Lebanon by Israel led to the displacement of thousands of villagers, mainly Shias. Many of them first settled in Beirut’s eastern suburbs, before they were forced to flee again during the civil war, which led to the partition of the capital. They then settled in the Southern suburbs of the city, now commonly called ‘Dahiye’. As a result, the area saw the solidification of a Shia community, and an even further densification of informal, mainly illegal constructions in Ouzai.

Today, the area is more heterogeneous than the common monolithic understanding of ‘Dahiye’ implies. In digging into Ouzai’s complex, multilayered history, the artist hopes to extend the reflection to larger ideas evoked by such a space. Indeed, Ouzai is a small area, which carries its own history, but somehow it seems to encompass the quintessence of what is facing all of Lebanon right now – issues of sectarian division, displacement, community, urban transformation, density of construction, inequality, reconciliation, etc.